Even in former times, Bayreuth had its share of connoisseurs who appreciated the specialities of its cuisine and its beer. Several reports about culinary locations have also been chronicled. A few of them are collected here.

Well-known Bayreuth gourmets

Bayreuth is known for its musical greats and also for philosophers who have made the city their home over the years. However, some of them fell in love not only with the city and its unspoilt, picturesque surroundings, but also with the delights of traditional Franconian cuisine.

Richard Wagner

Richard Wagner enjoyed his food and drink. In her diaries, his wife Cosima often spoke of her husband’s “dietary failings”. He was particularly fond of Bayreuth’s beer.

As a regular guest at the “Angermann” inn, he would often come there after his walks with his dog Russ and sit down at the so-called coachman’s table, smoke a cigar and drink a glass of beer. He usually did this slowly and in silence. He liked to eat light meals with bread there and had his own cutlery with ivory handles and his own two plates. He would also only drink from a glass reserved for his use. The tradition of regular customers using beer mugs reserved for their personal use still exists today in some inns.

Wagner, being the gourmet he was, would also dine on the lobster platter with figs at the “Hotel Goldener Anker”, and is said to have been very partial to Franconian “sauerbraten” (marinated roast beef) at the “Eule” restaurant.

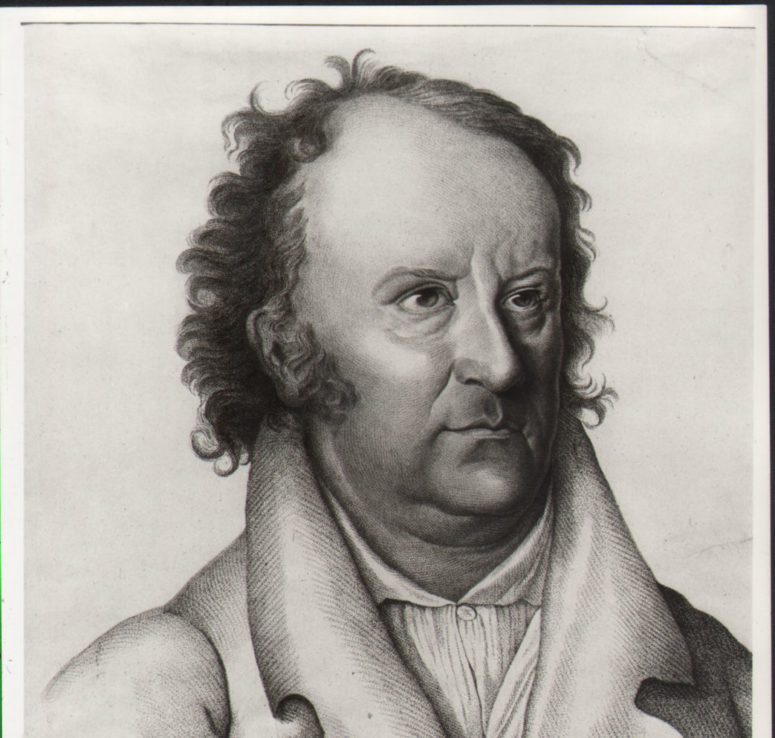

Jean Paul

„I am strangely healthy. Thanks to Bayreuth’s beer …“ These were the words of Jean Paul, who on occasion had his friend Osmund send him a keg from Bayreuth to Weimar and Meiningen.

He took great pleasure in the thought of moving to Bayreuth: “But once I’m in Bayreuth – heavens, how I will drink!” He too was fascinated by Bayreuth as a culinary centre.

In his work “Levana oder Erziehlehre” (Levana or Theory of Education), the following can be found on Bayreuth’s beer: “Thank God that you – like me – do not live in Saxony or in the Saxon Vogtland, but in Bayreuth, closest to the best beer – Champagne beer.”

The city had only one disadvantage for him: There were so many locals living there …

Culinary locations in Bayreuth

Places of culinary excellence, traditional Franconian cuisine and home-brewed beer can be found in many corners of the city these days. But where did people go to treat themselves to a fine meal in Richard Wagner’s day? Some of the culinary locations still exist today, and you can imagine eating “sauerbraten” for Sunday lunch with the poets and thinkers of the time.

Redoutenhaus, Opernstraße

In Margravine Wilhelmine’s day, opulent theatre performances and lavish festivities were held here. At these baroque feasts, all the dishes were served on the table at the same time: soup, various kinds of fish and meat, a variety of vegetables and even the desserts. A feast was always presented as a complete work of art.

On the occasion of the wedding of Wilhelmine’s daughter Friederike Sophie to the Duke of Württemberg, the following food was also served to the public: an ox, two stags, eight sheep and a fountain from which wine and beer flowed. For safety reasons, no knives were allowed. One can only imagine how the meal then proceeded.

Wittelsbach Fountain, Opernstraße

On 31 July 1914, one day before the First World War broke out, the Wittelsbacher Brunnen (Wittelsbach Fountain) was inaugurated. The festive menu served at the Hotel Reichsadler to mark the occasion was so opulent that Bayreuth’s social democrats were still gossiping about it in their party committees five years later.

Hotel Goldener Anker

The hotel has been in the hands of the same family for generations. The history of the property can be traced back to 1500; since that time, the family has held the rights to host guests and to brew beer.

From 1753 onwards, the family was granted the rights to run a hotel, and the hotel was named “Goldener Anker”. Mark Twain, a guest at the hotel, had the following to say about it: In the “Goldener Anker”, one could dine superbly. Then he corrected himself and said that one could watch how others dined there superbly.

In 1895, for the occasion of the birthday of the Bavarian Prince Regent Luitpold, the “Bayreuther Tagblatt” reported that the city council hosted a dinner for 80 people there; An enormous banquet including Russian caviar, broth, Rhine salmon, macaroni, various salads, game pâté, wild boar ragout, Brussels sprouts, veal roulade, goose breast, turkey stuffed with truffles, various compotes, cheese and frozen confectionery.

Hotel Schwarzes Ross, Ludwigstraße 2

This establishment, no longer in existence, once housed famous guests such as Engelbert Humperdinck and Albert Schweizer, who embarked on his Bach biography here – despite the noise from the town’s famous beer hall located there.

Neues Schloss, Ludwigstraße

In the days of the margraves, there were numerous festivities in the New Palace — a true culinary paradise. For the margraves, only the best was (just) good enough. We know, for example, that it had around 600 employees in 1755. 14 chefs were employed there, and there was a court caterer and even a truffle hunter. It is said that from 1730 to 1755 about 35,000 game birds and animals were shot.

At the beginning of the 18th century, a menu for an ordinary midday meal on an ordinary Tuesday included the following dishes: potage of herbs and morels, beef and veal, dried meat, salads, lark’s breast and roast duck.

When distinguished guests were expected, the selection was of course even more refined: in 1743, for example, Margaret, a farmer’s wife who delivered squab (young pigeon), eggs and herbs to the castle, reported a distinguished visitor from Berlin. The farmer’s niece was employed in the kitchen of the palace and had the following to report:

“Special horseback teams were sent to deliver truffles from Alsace; local venison was prepared in a new, refined way with exotic fruits and spices that could only be obtained from Nuremberg or Augsburg merchants. There were plenty of foreign wines to go with it. At very festive banquets, so-called show dishes were also served. These were decorated with sugar sculptures and fountains from which precious stones flowed. The more elaborate, the better. There were also show dishes that were simply painted porcelain.”

The margravial cuisine was strongly meat-based, relying heavily on game, poultry, and beef in various forms. Due to this diet, many members of the higher social classes often suffered from gout.

The lower classes in those days had a rather frugal diet: the common man seldom had meat on his plate. Flour dishes, pulses, turnips, cabbage and cereal mash made from oats or barley were the order of the day. To drink, there was water, diluted with wine for its antiseptic properties, or often home-brewed beer and milk.

Mann’s Bräu, Friedrichstraße - The tradition of the “Beckenbrauer”

First of all, perhaps, some general information about beer-brewing in Bayreuth: Since brewing was not considered a “proper trade”, in Bayreuth, every full citizen of the city was allowed to brew his own home-brew annually in the city brewery – under the supervision of the city’s brewmaster, of course.

Gradually, the bakers became specialists in this sideline. At the beginning of the 20th century, a “Beck” brewed about five to six hectolitres per year, which was served to gourmets in the tavern, the so-called “Zechstube”.

One of these “beck” families was the Mann family in Friedrichstraße. They brewed so-called “Schenkbiere” (beer for serving) and “Lagerbiere” (beer for storing) from 1823 onwards. Their “Doppelbock” was legendary. This is still available today – but brewed by Becher Bräu in the Altstadt.

Beer was not brewed from May to September. During these months, the cooling of the beer could not be guaranteed. From 1911 onwards, the Mann family dedicated themselves solely to brewing. They had completely given up baking.

Very close to “Mann’s Bräu”, a “Buschenschenke” open its doors again today: The “Bäckerei Lang” has revived the old tradition and brews its own beer four times a year, the dates can be found on their website: Buschenschänke – Lang Genusswelt (baeckerei-lang.de). For over 250 years the family has had the right to brew beer, at the end of the 18th century brewing equipment was mentioned for the first time and from the beginning of the 19th century, beer was served to customers.

The “Bauernwärtla”, Sophienstraße

Another well-known “Beckenbrauer” was Georg Bauer, who ran the „Bauernwärtla“ in Sophienstraße. The „Wärtla“ (a diminutive form of “Wirt“, or landlord) opened at the beginning of the 20th century and soon became very popular. The so-called “laboratory” – the bar – earned its name because the landlord conducted all kinds of experiments with beer. Many a cloudy brew was disguised with a dark colouring agent. Some guests were served a very individual drink, mixed from a wide variety of barrels.

He was also well known for his jokes and sayings. When a rather pushy Prussian asked for a “little blonde” (beer), he is said to have replied mockingly: “Just wait until you’re a bit thirstier, and then drink a big one”. The Bayreuth local also had a heart for young people, and many a grammar school pupil ended up with a hangover for a ridiculously low price. Even at the age of 90, Georg Bauer was still a cheerful beer drinker. The “Bauernwärtla” is still a pub to this day.

Bayreuth’s artists’ pubs – today and in former times

In Wagner’s day, the “Angermann” was an institution. Artists and musicians gathered there after rehearsals for the festival. The nights at the pub were often just as long as the rehearsals for the festival.

The artists also referred to the Angermann as “the catacombs”. A long corridor led to very modest, narrow and low guest rooms. On the first floor was an equally unglamorous hall. The guests were seated at simple long wooden benches and tables, and Weihenstephan beer was served there.

The Angermann soon became an attraction for visitors to the Bayreuth Festival. The inn was in such great demand during the festival at times that the crowds, tankards in hand, not only filled the rooms and the outside areas, but also the entire pavement and the street to the houses opposite (according to an observation of Hans Bertolo Brand, a photographer).

Right next door there was another inn, the “Weisse Lamm”, which was equally well frequented during the festival season. To make way for the new post office, both houses were demolished in 1892.

Before their demolition, Christian Sammet, one of Bayreuth’s real characters, secured some of the furnishings and housed them in his café at the Old Palace. His father had already run a coffee and beer bar there. Café Sammet served a few curiosities: Wotan ham, Brünnhilde steak, Mime eggs or Siegmund asparagus spears.

Even before 1900, the café was a gastronomic highlight for the festival’s haute cuisine: “Sammet’s Musenheim” was awarded a“Baedeker” star. For the entertainment of guests, there were musical events, vaudeville guest performances and film screenings.

Sammet also played a birthday serenade on the trumpet for Cosima Wagner, but she was not so amused and rejected this musical homage. When he carried on playing regardless, he was reported for disturbing the peace. At the end of 1908, Café Sammet closed its doors after the premises became the property of the Bavarian state.

The “Eule” in Kämmereigasse already existed in Richard Wagner’s day. The master bookbinder Christian Senfft reported that Richard Wagner had asked him for directions to the Eule. He had heard that there was a restaurant with particularly good beer in a small lane near the Stadtkirche (City Church). Since the directions given were too complicated for him, Wagner simply decided to take the master bookbinder with him, in his working clothes, for an evening beer. Wagner then also picked up the bill.

However, the Eule’s meteoric rise to fame as an artists’ pub only began after Richard Wagner’s death. What the Angermann was for him, the Eule was for his son Siegfried. The side room was even named after him.

During the festival, celebrities and artists alike met there. Numerous photographs on the walls bear testimony to this. From the 1970s onwards, the Eule began to fall out of favour. People met elsewhere.

After extensive renovation, the Eule has now been opening its doors again for a number of years, and welcomes its guests in the traditional manner once more.

For decades, the “Weihenstephan” in Bahnhofstraße enjoyed cult status among festival participants. Once bought and renovated by two world-famous Wagner singers and a theatre director, the pub quickly established itself as a meeting place for Wagnerians.

High on the Theta, a welcoming beer garden can be found, situated under magnificent old trees. During the Richard Wagner Festival, the popular beer garden becomes a meeting place for the artists and musicians. Sitting together, having a bite to eat and discussing rehearsals and performances is a regular evening activity during the festival season.

If you want to pay the beer garden a visit yourself, the best way to do so is combine your visit with a short hike.

Sources:

Mayer Bernd, Bayreuth G´schichtla

Rückel Gert and Kolb Werner, Stadtführer Bayreuth